Pilot Company, headquartered in Knoxville, Tennessee, is one of North America’s leading suppliers of fuel and the largest operator of travel centers. Its history spans over six decades, marked by strategic growth, partnerships, and a recent transition in ownership. Below is a detailed exploration of its history, rooted in available information and critically examined for clarity.

Henry McClure has 45 years of real estate experience of real estate transactions of all kinds. Most of my career has been dedicated Shopping Mall re-development, commercial leasing, commercial sales, Mixed-Use/TIF redevelopment and sales of residential and commercial real estate. I have played real advisory roles including but not limited, commercial and residential development, leasing, zoning, real estate tax valuation, platting issues and Brokers Opinions. #mcre1

Thursday, May 29, 2025

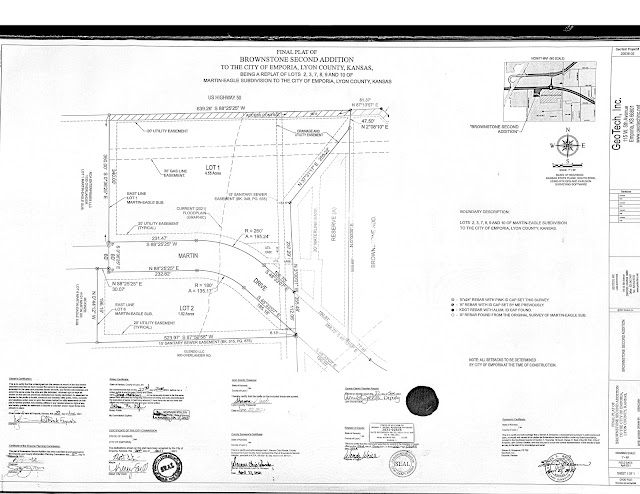

Emporia Travel Plaza welcomes Pilot @ Red Brick LLC

Founding and Early Years (1958–1970s)

Pilot Company was founded by James A. Haslam II in 1958. Born in 1930 in Detroit, Michigan, Haslam moved to Tennessee to attend the University of Tennessee, where he played football under coach General Robert Neyland, whose leadership principles later influenced his business approach. After serving in the U.S. Army and briefly working at Sail Oil, Haslam struck out on his own due to a non-compete agreement restricting him from operating in East Tennessee for three years.

On October 9, 1958, Haslam and his first wife, Cynthia, incorporated Pilot Oil Corporation, inspired by an insurance ad Haslam saw while traveling in North Carolina. A month later, on November 20, 1958, they purchased their first gas station in Gate City, Virginia, for $6,000. This station, equipped with four fuel pumps, sold cigarettes and soft drinks. Haslam’s early strategy focused on Virginia and Kentucky, where he meticulously analyzed traffic patterns to select optimal locations for new stations. By 1965, Pilot owned 12 stations and was selling 5 million gallons of fuel annually. The company built its first convenience store in 1976, shifting its focus toward retail and convenience.

Expansion and Travel Centers (1980s–1990s)

In 1981, Pilot opened its first travel center, a pivotal move that catered to professional drivers and travelers with amenities like truck parking, showers, and food services. By 1988, Pilot began aggressively expanding its travel center network nationwide, opening its first location with an in-house fast-food restaurant, enhancing its appeal to on-the-go customers. This period marked Pilot’s transition from a regional gas station chain to a national travel center operator.

In 1993, Pilot entered a joint venture with Marathon Petroleum Company, renaming its truck stops Pilot Travel Centers. This partnership provided capital and expertise, fueling further expansion. By the late 1990s, Pilot’s growth attracted political scrutiny, particularly when Jim Haslam supported a failed metropolitan government initiative in Knox County, leading to his non-reappointment to the Knox County Public Building Authority in 1999.

Mergers and Partnerships (2000s)

In 2001, Pilot and Marathon formalized their partnership, creating Pilot Travel Centers, LLC. This allowed Pilot to leverage Marathon’s fuel supply chain while continuing to expand. In 2003, Pilot acquired the Williams Truck Stop chain, more than quadrupling its locations. In 2008, Pilot bought out Marathon’s interest and partnered with CVC Capital Partners, a private equity firm, to fund further growth.

A significant milestone came in 2010 when Pilot merged with the bankrupt Flying J, a rival truck stop chain, for $1.8 billion. The combined entity, Pilot Flying J, became North America’s largest travel center operator, with over 550 locations across 23 states and Canada, employing over 23,000 people. The merger preserved both brands’ identities, with Pilot and Flying J locations accepting shared fuel cards like Comdata and TCH. However, the merger also brought challenges, including integrating operations during the Great Recession.

Challenges and Controversies (2010s)

In 2013, Pilot Flying J faced a major crisis when its Knoxville headquarters was raided by the FBI and IRS over allegations of fuel rebate fraud. An affidavit implicated several sales employees and company president Mark Hazelwood in a scheme to defraud trucking customers. CEO Jimmy Haslam (Jim’s son) acknowledged the investigation, and by July 2013, a federal judge approved a settlement with affected trucking companies. The scandal damaged Pilot’s reputation but did not halt its growth.

In 2014, Pilot acquired a controlling stake in Mr. Fuel and merged its logistics arm with Thomas Petroleum to form Pilot Thomas Logistics, strengthening its energy logistics capabilities. In 2015, the Haslam family bought out CVC Capital Partners’ stake, regaining full ownership of Pilot Flying J’s convenience store operations.

Berkshire Hathaway Acquisition (2017–2024)

In 2017, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway acquired a 38.6% stake in Pilot Flying J, signaling confidence in its business model and future potential, particularly in serving electric and natural gas vehicles. In 2023, Berkshire increased its stake to 80%, with the Haslam family retaining 20% and control of daily operations. In January 2024, the Haslams sold their remaining 20% to Berkshire for an undisclosed amount, ending 65 years of family ownership. The sale followed lawsuits between the Haslams and Berkshire over the valuation of the final stake, settled out of court in early 2024. Berkshire committed to keeping Pilot’s headquarters in Knoxville, preserving its local economic impact.

Leadership Transitions

Jim Haslam led Pilot until his son, Jimmy Haslam, became CEO in the 1980s, serving for 25 years before transitioning to chairman in 2021. Shameek Konar served as CEO from 2021 until 2023, when Adam Wright, a Berkshire Hathaway veteran with experience at MidAmerican Energy, took over. Wright, a former NFL player, emphasizes faith, family, and community, maintaining a positive relationship with Jim Haslam, whose portrait still hangs in Pilot’s headquarters.

Recent Developments and Philanthropy

Pilot Flying J now operates nearly 900 locations across 44 states and six Canadian provinces, serving 1.2 million guests daily. It supplies 12 billion gallons of fuel annually, operates the third-largest fuel tanker fleet in North America, and is a major provider of biodiesel and renewable fuels. In 2023, Pilot partnered with General Motors to launch EV charging stations at select locations, positioning itself for the energy transition.

The Haslam family’s philanthropy remains a cornerstone of Pilot’s legacy. They donated $50 million to the University of Tennessee in 2014, naming the Haslam College of Business, and $10 million to UT Medical Center in 2023 to expand its emergency department. Jim Haslam’s 2020 book, Co-Piloting: Luck, Leadership and Learning That It’s All About Others, details Pilot’s history and his philosophy, with proceeds supporting local nonprofits.

Critical Perspective

Pilot’s growth from a single gas station to a national powerhouse reflects strategic acquisitions and adaptability, but it hasn’t been without flaws. The 2013 fraud scandal exposed weaknesses in corporate oversight, and the sale to Berkshire Hathaway raised questions about whether local control would persist. While Berkshire’s hands-off approach and commitment to Knoxville are reassuring, the Haslams’ exit marks the end of an era. Pilot’s pivot to EV charging and renewable fuels is forward-thinking, but its success will depend on navigating a competitive energy market.

If you’d like me to dive deeper into any aspect, such as specific acquisitions, leadership, or Pilot’s future in sustainable energy, let me know

Tuesday, May 27, 2025

NEW NEWS

Financial Situation and City's Efforts to Sell:

- The city has been actively looking for buyers for Hotel Topeka, but has not been successful in finding a buyer.

- The city has invested over $10 million in the hotel, including the purchase and renovations.

- The city expects a net operating loss of nearly $900,000 in 2025.

- City leaders aim to sell the hotel by the end of 2025.

- The city has been exploring various options to recoup the investment, including economic development grants and tax breaks.

- The city has requested additional funding for the hotel, which was approved by the Topeka City Council.

Hotel Topeka's Condition:

- The hotel is considered a "distressed asset" and has been losing money.

- The appraised value of the hotel has remained at $3 million since the city purchased it.

- Multiple developers have said it will take at least $15 million to renovate the hotel to become a flagship hotel.

Monday, May 26, 2025

Why Chambers of Commerce May Not Be Ideal [understatement] #mcre1

Key Points

- Research suggests Chambers of Commerce may not be ideal for managing economic development funds due to potential conflicts of interest.

- It seems likely that their focus on business advocacy could lead to biased fund allocation, favoring members over the broader community.

- The evidence leans toward them lacking the specialized expertise needed for transparent and accountable public fund management.

- There is some controversy around their ability to align with public interest goals, given their business-oriented priorities.

Public Fund Management Overview

Public fund management in economic development involves administering public financial resources to stimulate growth and benefit the community. It requires transparency, accountability, impartiality, efficiency, and compliance with legal frameworks to ensure funds are used equitably.

Why Chambers of Commerce May Not Be Ideal

Chambers of Commerce, primarily focused on advocating for their member businesses, may face conflicts of interest, potentially prioritizing projects that benefit members over broader community needs. They may also lack the expertise for managing large-scale public investments and the mechanisms for public disclosure, which could reduce accountability. Their business-oriented priorities might not align with public economic development goals, such as supporting underserved communities or non-business initiatives.

Best Practices for Management

Best practices include using independent governance structures, public reporting, standardized processes, regular audits, and community input to ensure effective and equitable management of public funds.

Survey Note: Detailed Analysis of Public Fund Management and Chambers of Commerce

This survey note provides a comprehensive analysis of public fund management in the context of economic development and evaluates why the Chamber of Commerce might not be the ideal entity to manage such funds. The analysis is informed by a thorough review of available resources, including academic publications, organizational insights, and social media discussions, as of 01:22 PM CDT on Monday, May 26, 2025.

Understanding Public Fund Management in Economic Development

Public fund management refers to the processes and systems governments use to manage their financial resources, including budgeting, accounting, and auditing, specifically for economic development initiatives. Economic development funds are typically taxpayer-derived or government-controlled resources aimed at stimulating local or regional economies through initiatives such as business grants, infrastructure projects, or workforce training programs. These funds are intended to benefit the entire community, requiring a high level of transparency, accountability, impartiality, efficiency, and compliance with legal and regulatory frameworks.

Research from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) highlights the importance of public investment management (PIM) within public financial management, noting that public investments, such as infrastructure projects, are crucial for economic development but require careful planning, allocation, and implementation . The World Bank emphasizes the need for strong institutional capacity to improve the quality and impact of public investments, particularly in low-income countries where efficiency is estimated to be 40% below advanced economies . This underscores the complexity and specialized skills required, which are often managed by dedicated public sector entities.

Role and Functions of Chambers of Commerce

Chambers of Commerce are associations or networks of businesspeople designed to promote and protect the interests of their members through advocacy, networking, and various services . They exist at local, regional, and national levels, focusing on building communities, promoting them, ensuring future prosperity via a pro-business climate, representing the employer community, and reducing transactional friction . In the United States, membership is typically voluntary, and their primary mission is to support member businesses, as opposed to managing public funds, which is more common in compulsory models in countries like Germany .

Their role in economic development often involves advocacy for business-friendly policies, hosting networking events, and sometimes facilitating economic strategies, but historical shifts have seen economic development roles being pulled into separate organizations, such as Economic Development Corporations (EDCs) . This suggests a traditional focus on business support rather than public fund management.

Reasons Why Chambers of Commerce May Not Be Ideal for Managing Economic Development Funds

Several factors suggest that Chambers of Commerce may not be suited for managing economic development funds, based on their structure, focus, and capabilities:

- Conflicts of Interest: Chambers represent their member businesses, which could lead to biased allocation of funds. For instance, they might prioritize projects benefiting members, such as local business grants, over broader community needs like public infrastructure, potentially leading to favoritism . This conflict is particularly evident in their advocacy role, which may not align with impartial public fund management.

- Limited Expertise: Managing public funds, especially for large-scale investments, requires specialized skills in planning, allocation, and implementation, as well as compliance with legal and regulatory frameworks. Chambers, focused on networking and advocacy, may lack this expertise. The World Bank's work on PIM diagnostics and assessments, such as the PIM Assessment (PIMA) developed with the IMF, highlights the need for specialized tools and institutional arrangements, which Chambers may not possess .

- Inadequate Transparency: As private organizations, Chambers may not have robust mechanisms for public disclosure, which is critical for public fund management to ensure accountability. Public reporting and audits, as recommended by best practices, are typically managed by government entities with public oversight, not private business associations .

- Misaligned Priorities: The Chamber’s focus on business interests, such as promoting member businesses and ensuring a pro-business climate, may not align with broader public economic development goals. For example, they might overlook initiatives supporting underserved communities or non-business projects like education, which are crucial for equitable growth . This misalignment is evident in historical shifts where economic development was separated from Chamber roles to focus on broader community benefits .

Supporting Evidence from Case Studies and Discussions

While direct case studies of Chambers managing economic development funds were not found, indirect evidence from organizational roles and historical shifts supports the above reasons. For instance, a case study from Independent Dealer mentions a local Chamber involved in business growth initiatives, but it does not indicate managing public funds, focusing instead on advocacy and networking . This reinforces that Chambers are better suited for business support rather than public fund management.

X posts also provide context, with

@g_gzn

noting government efforts to enhance public financial management for economic development, emphasizing transparency and efficiency , and @resfoundation

highlighting the growth impact of public investment . These discussions underscore the public sector's role, contrasting with Chambers' private focus.Best Practices for Managing Economic Development Funds

To ensure effective and equitable management, best practices include:

- Independent Governance: Using neutral bodies like public economic development agencies or oversight boards to reduce conflicts of interest, ensuring impartial allocation.

- Public Reporting: Publishing detailed reports on fund allocation, beneficiaries, and outcomes, accessible to all stakeholders, to enhance transparency.

- Standardized Processes: Implementing clear, merit-based criteria for fund distribution with documented evaluation procedures to ensure fairness.

- Audits and Oversight: Conducting regular independent audits to verify compliance and proper use of funds, maintaining accountability.

- Community Input: Involving diverse stakeholders, including residents and non-profits, in setting priorities to ensure funds reflect public needs, promoting inclusivity.

These practices are supported by IMF and World Bank guidelines, emphasizing the need for specialized systems and public oversight, which Chambers may not be equipped to handle .

Table: Comparison of Chamber of Commerce and Public Entities for Fund Management

Aspect | Chamber of Commerce | Public Entities (e.g., Economic Development Agencies) |

|---|---|---|

Focus | Business advocacy, member support | Public interest, community-wide benefits |

Conflicts of Interest | High, due to member representation | Low, with independent oversight |

Expertise | Limited, focused on networking and advocacy | High, with specialized PIM and financial management skills |

Transparency | Potentially inadequate, private organization | High, with public reporting and audits |

Alignment with Goals | Business-oriented, may miss broader needs | Aligned with public economic development objectives |

This table summarizes the key differences, highlighting why public entities are better suited for managing economic development funds.

Conclusion

While Chambers of Commerce play a valuable role in economic development through advocacy and business support, their structure and priorities, focused on member interests, may not align with the stringent requirements of public fund management. The potential for conflicts of interest, limited expertise, inadequate transparency, and misaligned priorities suggest that dedicated public entities or independent boards, with their capacity for impartiality and specialized skills, are better equipped to ensure fairness, transparency, and alignment with community-wide goals.

Key Citations

LOOK closely. [#mcre1] Key Principles of Public Fund Management:

What is Public Fund Management?

Public fund management involves the responsible administration, allocation, and oversight of taxpayer-derived or government-controlled financial resources to achieve public objectives, such as economic development, infrastructure improvement, or job creation. It requires transparency, accountability, and impartiality to ensure funds are used effectively and equitably for the broader community’s benefit.

Key Principles of Public Fund Management:

- Transparency: All decisions, criteria, and outcomes (e.g., who receives funds and why) must be publicly disclosed to maintain trust and allow scrutiny.

- Accountability: Managers are answerable to the public and government for how funds are spent, with mechanisms like audits and reporting to prevent misuse.

- Impartiality: Funds must be allocated based on merit and public benefit, not favoritism or private interests.

- Efficiency: Resources should be used to maximize impact, aligning with strategic goals like economic growth or community welfare.

- Compliance: Fund management must adhere to legal and regulatory frameworks governing public resources.

Why Public Fund Management Matters for Economic Development Funds:

Economic development funds are often public resources aimed at stimulating local or regional economies through initiatives like business grants, infrastructure projects, or workforce training. Mismanagement can lead to wasted resources, inequitable outcomes, or loss of public trust. When an entity like the Chamber of Commerce manages these funds, the following issues related to public fund management may arise:

- Conflicts of Interest (as discussed previously): The Chamber’s focus on member businesses could lead to biased allocation, violating impartiality. For example, favoring member-owned businesses over non-members or prioritizing projects that benefit influential stakeholders over community-wide needs.

- Impact: Undermines public trust and diverts funds from high-impact projects.

- Limited Expertise: Chambers may lack the specialized skills or systems needed for rigorous public fund management, such as grant evaluation, financial auditing, or compliance with government regulations.

- Impact: Increases the risk of mismanagement or inefficient use of funds.

- Inadequate Transparency: As private organizations, Chambers may not have robust mechanisms for public disclosure, making it harder for taxpayers to see how funds are used.

- Impact: Reduces accountability and raises suspicions of favoritism.

- Misaligned Priorities: The Chamber’s advocacy for business interests may not align with the public’s broader economic development goals, such as supporting underserved communities or non-business initiatives (e.g., public infrastructure or education).

- Impact: Funds may not address critical community needs.

Best Practices for Public Fund Management in Economic Development:

To address these concerns and ensure effective management, the following practices are recommended:

- Independent Governance: Use a neutral body (e.g., a public economic development agency or oversight board) to manage funds, reducing conflicts of interest.

- Public Reporting: Publish detailed reports on fund allocation, beneficiaries, and outcomes, accessible to all stakeholders.

- Standardized Processes: Implement clear, merit-based criteria for fund distribution, with documented evaluation procedures.

- Audits and Oversight: Conduct regular independent audits to verify compliance and proper use of funds.

- Community Input: Involve diverse stakeholders (e.g., residents, non-profits, and businesses) in setting priorities to ensure funds reflect public needs.

Relevance to the Chamber of Commerce:

While the Chamber of Commerce can play a valuable role in advocating for businesses and fostering economic growth, its structure and priorities may not align with the stringent requirements of public fund management. For instance, a Chamber might excel at networking or promoting local businesses but lack the impartiality or expertise needed to equitably distribute public funds. Assigning this responsibility to a dedicated public entity or an independent board with public fund management experience could better ensure fairness, transparency, and alignment with community-wide goals.

If you have specific reasons or scenarios related to why the Chamber might not be ideal for managing these funds (e.g., one of the four reasons you mentioned initially), or if you want me to explore a particular aspect of public fund management (e.g., case studies, regulations, or alternatives), please let me know, and I’ll provide a more targeted response!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)